More Than Lyrics and Style

Rethinking church music as a formational act, not just a stylistic choice

When it comes to what and how we sing in gathered worship, the conversation often stops at two main points: lyrical content and musical style. Are the words biblical? Is the music contemporary or traditional? While these are valid considerations, they overlook another essential aspect.

Beyond the Usual Worship Debate

In a culture trained to evaluate church music by its words or genre, there is a missing aspect. Steven Guthrie explores this in his chapter from Resonant Witness, a book he co-edited with Jeremy Begbie. Guthrie argues that congregational singing is not simply a symbol of unity but an actual enactment of it. When the Church sings together, it becomes “one voice composed of many voices.” He writes, “Congregational song is not a metaphor of the socially and ethnically diverse church. It is this gathered body; or at least, this body’s voice, this body made audible.”1

If Guthrie is right, and I believe he is, then our conversations about church music should include more than just lyrics and style. We should be asking: What does our music do to us as a people? How does it shape us? What does it teach us, not only with its words but with its rhythm, structure, and form?

Singing as Enacted Unity

Congregational singing is not only about aligning with lyrical truth or achieving musical beauty. It reinforces the communal nature of gathered worship. It is a shared act that expresses mutual submission and unity, often without having to say so directly. In this sense, musical form matters. Harmony matters. The way music moves, repeats, and blends voices together matters. These musical elements are not neutral. They communicate. They shape. The music itself can affirm and reinforce the text. It can further shape our understanding of God’s order and purpose, even if not explicitly stated in the lyrics.

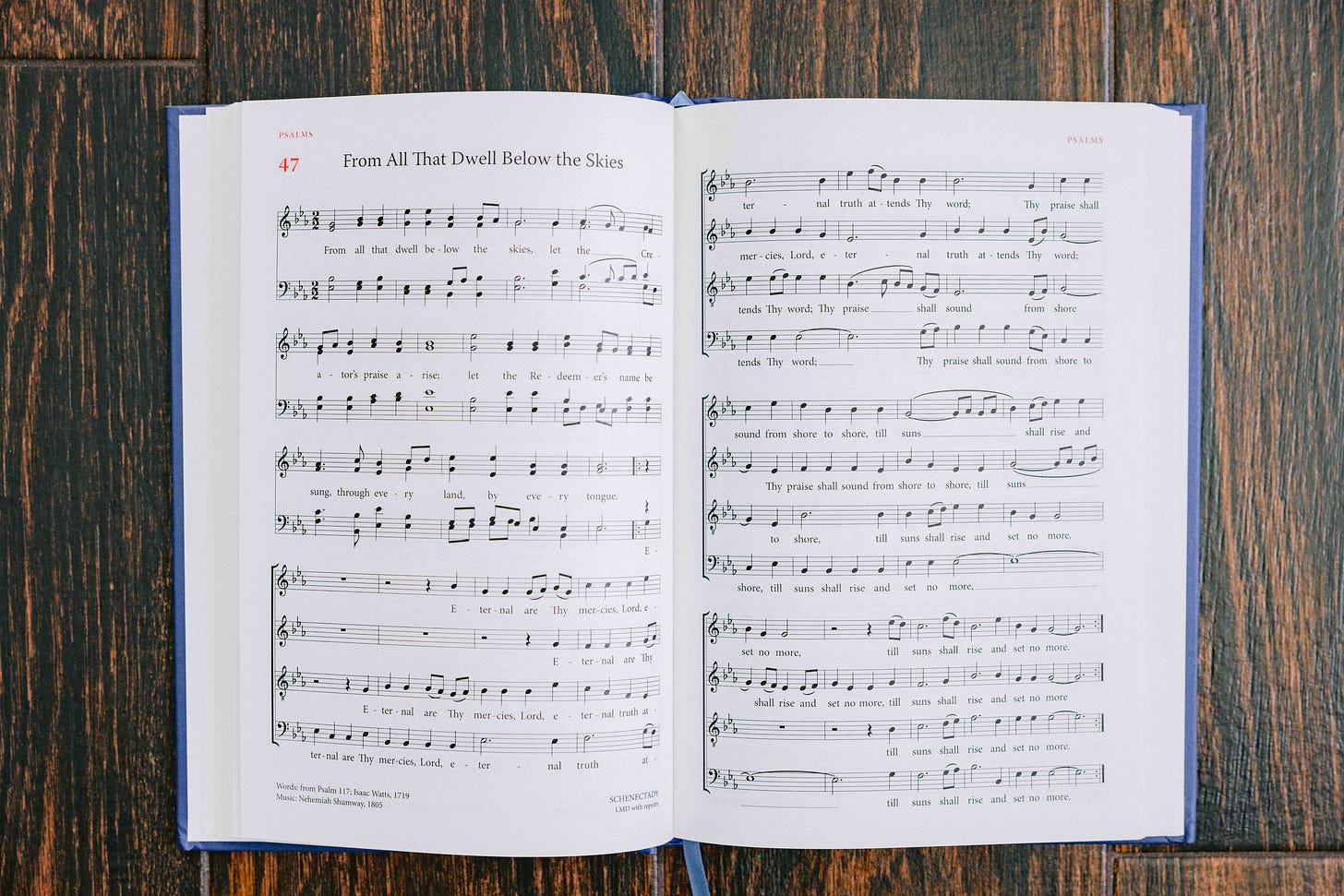

That is why well-crafted homophonic hymnody—music that is singable, rhythmically steady, and written for different vocal parts—can be so helpful. It is not effective because it is flashy or nostalgic, but because its structure helps enact unity. It gives shape to the body of Christ singing as one, made up of many parts. Beyond sounding beautiful, it proclaims a message to us and to the world.

Perhaps it is time to move the worship conversation in this direction. Instead of focusing on personal preference or musical style, we should consider whether our singing practices are helping us embody the community we are called to be. Are we choosing music that reflects the shared life of the Church, or are we settling for forms that lean toward individualism or simplicity?

Perhaps we need to train our people in joyful music literacy so we can better recover the richness of singing in harmony, where different voices come together to form a unified whole. Maybe we should expand the variety of musical forms we use in worship so that our congregational singing reflects the theological and communal depth we believe in. Music can teach, form, and shape us, not just through lyrics, but through the very act of singing together.

If God has embedded His glory and truth into all of creation, then our music should reflect that same glory in every aspect, not just in what we sing but in how we sing it.

More Than Praise

“Through Congregational song the Church not only proclaims the Kingdom of God but participates in its reality,” writes Christopher Ellis. For the modern Christian trained to see singing in church as merely praising God, this statement must seem odd, even if the reader finds it interesting or encouraging. Ellis is right to frame congregational song as we…

Steven R. Guthrie, “The Wisdom of Song,” in Resonant Witness: Conversations Between Music and Theology, ed. Jeremy S. Begbie and Steven R. Guthrie (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2011), 398.